Overview Of Federal Permitting Timelines For Locatable Mineral Projects On Public Lands

Introduction

For the last several years, Congress has focused on how the time-consuming and costly permitting process delays projects that require a federal permit. Many congressional lawmakers recognize there is an urgent need to streamline the permitting process for building new transmission lines, roads, and pipelines; developing wind and solar projects; exploring for minerals and constructing new mines; and other types of projects.

Permit streamlining was discussed during the March 12, 2025 Senate Energy and Natural Resource Committee hearing to consider several critical minerals and mining bills. Two of the witnesses told the committee that permitting delays stem mainly from the time it takes federal agencies to prepare Environmental Impact Statements (EIS) for proposed mining projects pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). NEPA litigation was also cited as significantly delaying permitting and creating considerable uncertainty that chills investment in domestic mineral exploration and mining projects.

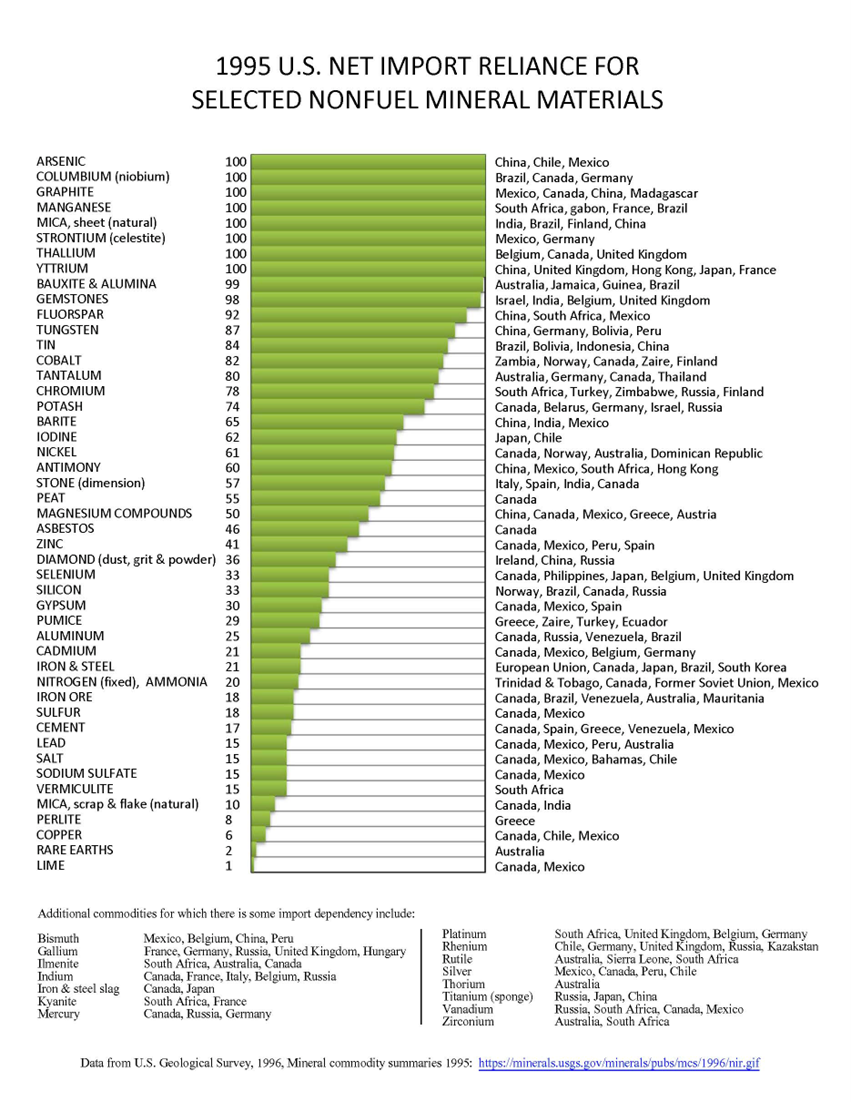

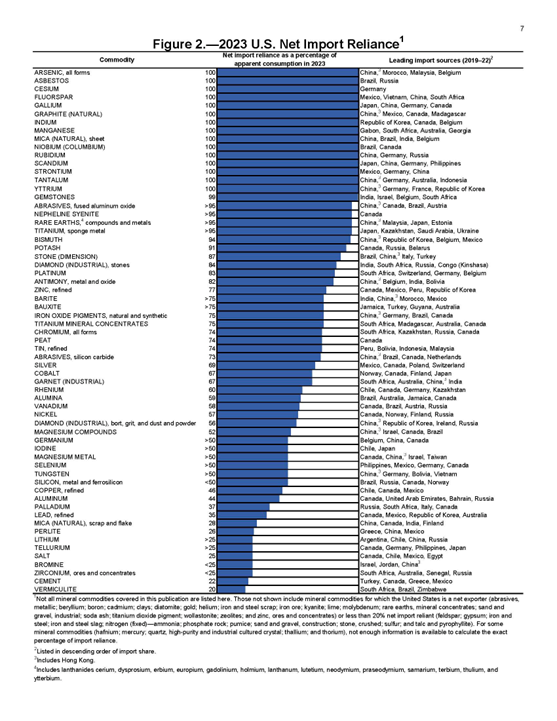

Permitting delays are recognized as one of the reasons the U.S. has become dangerously dependent on foreign minerals – especially minerals imported from China. Figure 1 (at the end of this document) presents data from the U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS’) Annual Mineral Commodity Summaries that show how U.S. mineral imports have soared since 1995 when the country was 100 percent reliant on imports for only eight minerals. In 2023, the U.S. was 100 percent reliant on imports of 15 minerals and was over 50 percent reliant on foreign sources for another 49 minerals.

The reasons for this alarming increase in mineral import reliance include the following:

- Because Congress stopped funding the U.S. Bureau of Mines (USBM) in 1996, the country no longer has a centralized group of mining and mineral processing experts who can advise Congress and Executive Branch policymakers on mining issues and perform important mining and mineral processing Research & Development to improve mining methods, enhance mineral recoveries, minimize environmental impacts from mining, and develop innovative new technologies to advance mining, mineral processing, and materials recycling.

- Since 1995, permitting has become significantly more difficult and time consuming due in large part to the frequency of NEPA litigation, which has caused federal agencies to prepare increasingly complex and lengthy EIS in an attempt to make them less vulnerable to appeals and litigation; and

- Lands containing identified mineral deposits like the Twin Metals copper-cobalt-nickel deposit in Minnesota have been put off-limits to mineral exploration and development. Sequestering lands with known mineral deposits or that have high mineral potential prevents the U.S. from responsibly developing its mineral endowment. Today, out of the 600 million acres of reserved public lands, roughly 400 million acres are set aside for conservation and preservation purposes and are thus functionally off-limits to mineral exploration and mining. According to former Department of the Interior Solicitor, John Leshy, during the period from 1980 to 2020, the acres of U.S. conservation and preservation lands grew from 250 million to 400 million 1.

Mineral Project Permitting Timelines

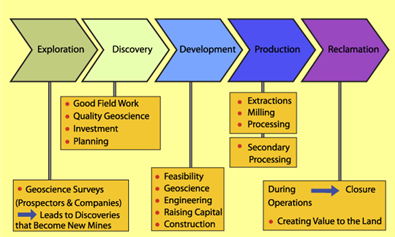

Evaluating permitting timelines for mineral projects requires an analysis of the permitting steps for the entire exploration – mining lifecycle. As shown in Figure 2, there are five phases of the Mining Lifecycle: Exploration, Discovery, Development, Production, and Reclamation. Mineral exploration and mining companies must obtain federal and state permits throughout this entire lifecycle before they can commence each phase. Permitting is thus an iterative process. Just as there are multiple phases of the exploration-mining lifecycle, there are multiple phases of permitting. Therefore, in considering the time it takes to permit a mine, each permitting phase needs to be aggregated into a total permitting timeline.

The Bureau of Land Management’s (BLM’s) 43 C.F.R. Subpart 3809 surface management regulations govern all mineral activities on BLM-administered lands that are subject to the U.S. Mining Law2. These regulations require that all mineral exploration and mining projects comply with the mandate in the Federal Land Policy and Management Act3 to prevent unnecessary or undue degradation (UUD) as specified in FLPMA Section 302(b).

Exploration-Discovery-Development Phase Projects

Permitting of the initial exploration phase is fairly straightforward and efficient. Initial exploration projects that create less than five acres of surface disturbance on BLM-administered lands must submit a Notice pursuant to 43 CFR 3809.300 - 43 CFR 3809.336 to BLM before conducting any surface-disturbing activities including building exploration drill roads and drill pads. BLM has 15 days to review the Notice and to advise the operator if more information is required before they are authorized to commence work. Operators typically retain a BLM-approved archaeologist to survey the proposed disturbance areas to identify any cultural resources that should be avoided during the exploration activities. The operator must also provide BLM with financial assurance (a reclamation bond) to guarantee that the exploration site will be fully reclaimed.4

Discovering a mineral deposit and delineating its boundaries and grade (the development phase) almost always requires drilling hundreds to thousands of drill holes that create more than five aces of surface disturbance. To move from the initial five-acre exploration phase to the discovery and development phases requires operators to obtain BLM’s approval of an Exploration Plan of Operations (EPO) for mineral activities that disturb more than five acres of BLM-administered lands. BLM deems their decision to approve a Plan of Operations a Major Federal Action that requires the agency to prepare a NEPA document – typically an Environmental Assessment (EA) prior to approving an EPO. Operators must provide site-specific environmental baseline data on a wide range of topics that BLM must evaluate in the EA including but not limited to wildlife, vegetation, threatened or endangered species of wildlife and plants, geology, soils, cultural resources, air quality, surface water, groundwater, and socioeconomics. During preparation of an EA (or an EIS), BLM must perform government-to-government consultation with potentially affected tribes pursuant to Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act.

The amount of time required for BLM to prepare an EA can vary depending on site-specific factors, BLM staffing levels and familiarity with mineral projects, and whether there are any community concerns about the proposed project. In Nevada, it typically takes BLM several months to a year to prepare an EA. But the amount of time it takes the operator to collect the required baseline data needs to be considered in evaluating the entire EA timeline. It is not unusual for baseline data collection to take up to a year because some data (like vegetation and wildlife data) can only be collected during specific seasons. In areas with surface water resources, BLM may require a years-worth of water quality data to document if there are seasonal variations.

The Aggregate EA Timeline for an EPO, defined herein as baseline data collection plus EA preparation, takes one to two years. Consequently, there can be a one to two year hiatus in exploration progress before an operator can resume exploration drilling after the Notice-level activities have created five acres of surface disturbance.

Mineral exploration is a data-dependent, iterative process. Before an operator can proceed with Phase 2, the data from Phase 1 must be evaluated to determine if proceeding to Phase 2 is warranted and, if so, where the next exploration roads and drill holes should be located. Although most operators try to build some flexibility into an EPO to allow them to explore for at least a couple of years, if the exploration results are favorable, modifying an EPO to authorize more surface disturbance and potentially to increase the size of the project boundary is eventually inevitable.

In order to minimize permitting delays that interrupt the exploration program, operators try to anticipate the need to submit a modification to their EPO and start the next round of permitting and EA preparation during Phase 1 activities. Operators may have to collect additional baseline data – especially if the Phase 2 modified EPO expands the project boundary into previously unanalyzed areas. Even if an operator has sufficient authorized surface disturbance to keep working while BLM is preparing the Phase 2 EA, there is still a gap in time between when the operator identifies areas that need to be tested and being authorized to commence the Phase 2 work. Because multiple exploration phases are typically required to delineate the extent of a mineral deposit, the permitting delays that occur several times during the life of an exploration project impede progress of the work needed to discover a mineral deposit that can be developed into an economically viable mine.

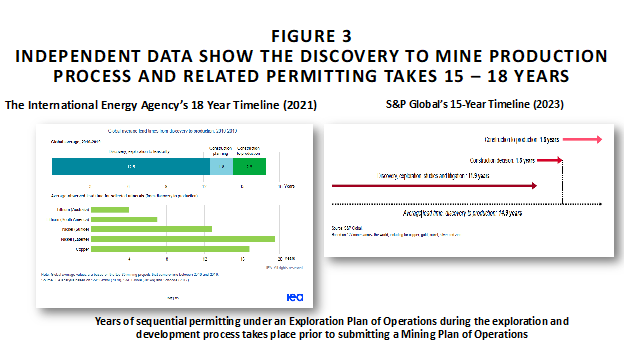

As shown in Figure 3, the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that the iterative process from exploration to feasibility takes 12.5 years. S&P Global has a similar timeline indicating it takes 11.9 years. Both estimates reflect the fact that exploration is time-consuming. The extensive drilling typically required to identify a valuable mineral deposit takes a long time. Permit-related delays in obtaining the sequential authorizations to drill in new areas and/or to create more surface disturbance adds to this timeline.

Streamlining the EPO permitting process would be an important step in reducing the overall permitting timeline from discovery to mine development because it would accelerate the discovery of mineral deposits that can become future mines. Cutting the exploration process timeline in half would lead to more discoveries of valuable mineral deposits that would ultimately reduce the Nation’s dependence on foreign minerals.

Some suggestions for ways to streamline the EPO permitting process include the following:

- Develop nationwide or general permits for projects that: propose typical exploration activities to build temporary roads and drill pads; manage drill water and cuttings with sumps or tanks; avoid cultural resources or other potentially sensitive resources; comply with the UUD mandate; and provide financial assurance.

- Develop statewide or nationwide programmatic NEPA document(s) for a typical EPO that can be used as a foundation to authorize EPOs with Categorical Exclusions (CXs) and Determinations of NEPA Adequacy (DNAs). Because most exploration drilling projects avoid sensitive resources and create temporary surface disturbances that can be fully reclaimed, they fit under the CX definition for “a category of actions that a Federal agency has determined normally does not significantly affect the quality of the human environment.”5

- Alternatively, develop project-specific EAs and authorize subsequent modifications to a project’s EPO using CXs and/DNAs.

- Expand the maximum number of allowable acres of surface disturbance under a Notice from five acres to ten acres. Require an EPO for projects that need to exceed a 10-acre Notice threshold.

- Create a Notice process for proposed exploration projects on National Forest System lands pursuant to the U.S. Forest Service’s (USFS’) surface management regulations for locatable minerals6 that mirrors the BLM’s Notice process. (Currently, the USFS requires an EPO for initial exploration activities that create less than five acres of surface disturbance.)

These suggestions are consistent with the permit by rule and permit streamlining directives in Section 5 of President Trump’s Unleashing American Energy Executive Order that requires “all agencies to prioritize efficiency and certainty over any other objectives, including those of activist groups, that do not align with the policy goals set forth in section 2 of this order or that could otherwise add delays and ambiguity,” as well as Section 9 on Restoring America’s Mineral Dominance.

According to the 1999 National Research Council/National Academy Sciences/National report, Hardrock Mining on Federal Lands, only about one in 1,000 mineral prospects become an economically viable mine.7 Consequently, discovering a mineral deposit that can support mine development is a very risky endeavor. This is one of the main reasons that reducing permitting delays for mineral exploration projects is critical in accelerating the mine discovery process to create a robust pipeline of mineral deposits that can become future mines. Streamlining the EPO permitting process represents the best opportunity to increase domestic mineral production in order to strengthen domestic mineral supply chains and reduce the Nation’s reliance on imports of foreign minerals.

Mining Phase Projects

Once an operator has done sufficient drilling and performed the extensive metallurgical tests and engineering studies necessary to suggest that development of a mine appears to be technically and economically feasible, that operator will submit a Mine Plan of Operations (MPO) to BLM to initiate the mine permitting process pursuant to 43 CFR 3809.400 - 43 CFR 3809.434. In conjunction with the MPO, operators must also submit detailed environmental baseline data beyond that required to prepare an EA for an EPO. For example, projects that have the potential to impact surface water or groundwater will require extensive hydrology modeling studies to identify and quantify potential impacts and ways to avoid or minimize those impacts. Mining projects also typically require air quality baseline data and dispersion modelling studies. Developing the environmental baseline and modeling studies required to support an MPO can take several years. The USFS’ environmental baseline data requirements for a proposed mine on National Forest System lands are similar.

BLM or the USFS must prepare an EIS to approve most MPOs. The Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) found that across all federal agencies, it takes 4.5 years to prepare an EIS from publication of a Notice of Intent to Prepare an EIS (NOI) in the Federal Register, which initiates the EIS process and the “NEPA clock” starts, to an agency’s final decision (e.g., the Record of Decision.).8 Litigation can add several years to the NEPA process and the initiation of project activities because courts frequently enjoin projects during ongoing litigation. The NEPA amendments in the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 (FRA)9 mandate that federal agencies complete an EIS within two years.

The Nevada BLM has a goal to complete an EIS for proposed mining projects (as well as for renewable energy and other types of projects) within one year of the NOI publication date. BLM NV follows a protocol for mining EISs that establish numerous steps for early coordination between the project proponent, BLM, cooperating agencies, counties, tribes and other stakeholders known as “pre-NOI planning.” 10

This protocol requires project proponents to submit all completed environmental and technical baseline study reports, including an initial assessment of environmental impacts and any necessary modeling data, before the NOI is published and the NEPA process starts. BLM uses this information to prepare an internal draft EIS that identifies the environmental impacts associated with the proponent’s proposed action and project alternatives and appropriate mitigation measures to avoid, minimize, or mitigate the project impacts. This protocol enables BLM Nevada to meet its goal to complete EISs within one year of publication of the NOI for many (but not all) projects.

Just as noted above for the Aggregate EA Timeline for an EPO, the Aggregate EIS Timeline for an MPO, needs to be defined as including the NOI pre-planning activities, plus the time required for the project proponent to collect the baseline data and perform all of the necessary technical and modeling studies, and BLM’s time to prepare the EIS. In aggregate, these steps take a minimum of several years. Although there may be opportunities to shave some time off of the MPO/EIS timeline, it probably is not realistic to significantly reduce the Aggregate MPO/EIS Timeline given the complexity of the detailed environmental baseline and technical studies that need to be completed for most proposed mining projects.

It is important, however, for agencies to adhere to the Sources of Information stipulated in the FRA, which states that a federal agency “may make use of any reliable data source [and] is not required to undertake new scientific or technical research unless the new scientific or technical research is essential to a reasoned choice among alternatives, and the overall costs and time frame of obtaining it are not unreasonable.” 11

For many years, the Washington, DC BLM office has had a bureaucratic process for reviewing and publishing Federal Register NOIs and Notices of Availability of the Draft and Final EIS documents for proposed mining projects that has created substantial delays that have added many months to the permitting timeline for some projects.12 Eliminating this bureaucratic process would be an obvious and meaningful way to shorten mine permitting timelines.

One potential opportunity to expedite the MPO/EIS process is for the project proponent to take the lead in preparing the EIS. The FRA NEPA amendments authorize “Sponsor Preparation” of an EA13 and an EIS and direct lead agencies to “prescribe procedures to allow a project sponsor to prepare an environmental assessment or an environmental impact statement under the supervision of the agency.” 14 Sponsor-prepared EIS may offer significant time savings for projects if the BLM office responsible for regulating the project is understaffed and/or unfamiliar with mining. BLM should make every effort to develop and finalize its procedures for sponsor-prepared NEPA documents (especially EIS) as soon as possible.

Last but not least, maintaining adequate BLM and Forest Service staffing levels to review and process permit applications efficiently to meet the FRA-mandated NEPA document timelines is critically important. These agencies should develop teams of permitting and mining experts and authorize the use of third-party expert permit reviewers to augment agency staff when necessary.

Although these suggestions may help streamline the permitting process for a proposed mining project, it appears that the greatest opportunity to decrease the overall amount of time it takes to discover and develop mineral deposits would be to focus on ways to expedite permitting for the exploration, discovery, and development phases of the mining lifecycle shown in Figure 2.

|

For more information please contact: |

|

|

David Kanagy |

Debra Struhsacker |

References

1. John D. Leshy, America’s Public Lands – A Look Back and Ahead, 67th Annual Rocky Mountain Mineral Law Institute, July 19, 2021. Back to content

2. 30 U.S.C. Sections 21a et seq. Back to content

3. FLPMA, 43. U.S.C. Sections 1701 et seq. Back to content

4. See 43 CFR 3809.500 to 43 CFR 3809.599. Reclamation bonds are calculated using the assumption that the operator is no longer willing or able to reclaim the site and that BLM and/or state regulators will have to perform the reclamation work. Bond amounts for large Nevada mining projects can be for hundreds of millions of dollars or more. Nevada BLM, the Humboldt Toiyabe National Forest, and the Nevada Division of Environmental Protection (NDEP) have a Memorandum of Understanding to co-manage the reclamation bonding program. Together, these agencies hold over $3 billion in financial assurance for Nevada exploration and mining projects. Back to content

5. 42 U.S.C. § 4336e Back to content

6. 36 C.F.R. Subpart 228A Back to content

7. National Research Council, Hardrock Mining on Federal Lands (Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1999), p. 24. Back to content

9. Public Law 118–5, June 3, 2023. Back to content

10. See Instruction Memorandum No. NV-2023-003 and the rescinded November 4, 2024 Instruction Memorandum on Plans of Operations Coordination Process issued by BLM’s Washington, DC office. Back to content

11. 42 U.S.C. § 4336(b)(3). Back to content

12. Delays in publishing Federal Register notices for proposed mining projects has been a chronic problem across numerous administrations of both political parties. Back to content

13. It is already common practice in Nevada for project sponsors to prepare EAs for proposed EPOs and other types of projects on BLM-administered lands. Back to content

14. 42 U.S.C. § 4336a(f) Back to content

Figure 1

Increases in Permitting Complexity and Timelines, the Demise of the U.S. Bureau of Mines, and Land Withdrawals have Resulted in Skyrocketing U.S. Mineral Import Reliance Back to content

Today, the U.S. is Dangerously Reliant on China and Other Foreign Adversaries For Many Minerals

Data from the 1995 and U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS’) Annual Mineral Commodity Summaries

Figure 2. The Five Steps in the Mining Lifecycle15